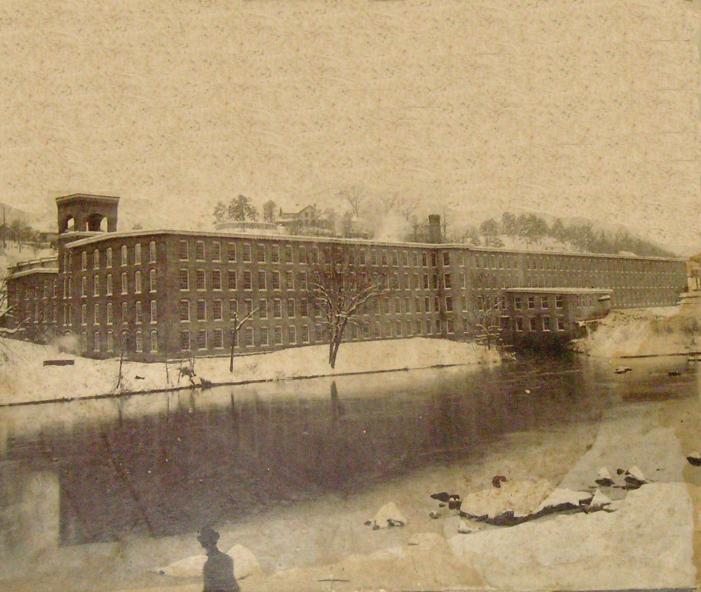

Even most of us who grew up around

and in sight of the textile mills took them for granted.

The huge brick buildings, 4, 5 or 6 stories high, just

seemed like part of the natural landscape that had

always been there. The mills and what went on in them

were anything but natural and simple. In reality, the

workings of a textile mill, even back to the early

1900’s, was an extremely complicated mechanical system.

Even today, there are few, if any factories or

industries that are as mechanically complicated as a

textile mill was in the 1900’s. If we look at how

difficult it was to start, build and operate a textile

mill we can get a better understanding and

appreciation of them. Unfortunately, this new found

appreciation comes almost too late because most of the

industry and the big mills are gone forever.

The rural locations where most of the southern mills

were built in the late 1800’s were mostly woods or at

best, farmland. The sites, back then, were chosen to be

next to a river or large creek to provide a source of

water power to drive the mill’s machinery. Once the site

was picked, the area for the mill and its foundations

had to be excavated and leveled. The area was usually

several acres in size.

The steam shovel had been invented back then but was not

widely available. Probably, the great majority of the

earth grading and foundation excavation was done by men

using picks and shovels and horses and mules pulling

drag pans. A drag pan was a small dirt scoop that was

pulled behind a horse or mule like a plow. It did not

hold much dirt. Thousands upon thousands of drag pan

trips would have to be made in grading the site for a

typical mill.

Men and horses

using drag pans. Location unknown.

Once the site had been graded, the construction of the

mill could be started. However, the design and planning

for the mill had started long before this. The mill was

built as an integrated system for the sole purpose of

making cloth on a large scale. Everything about the

design of the mill was devoted to that fact. The

arrangement of the floors, the purchase and location of

all the machinery, getting power from the water - all

had to be considered and precisely determined. Thousands

of details had to be decided. The company, Lockwood and

Greene, which still exists, designed some of the early

buildings at Pacolet Mills.

Each mill that was built is a testimony and tribute to

all those unknown and unheralded men of every occupation

that had a part of making an idea become a reality.

There were carpenters, brick masons, stone masons,

engineers, mill wrights and many, many others.

Getting the raw materials for building the mill was a

huge and expensive hurdle. First, someone had to

determine just how much and what size material would be

required. Secondly, a source had to be found for the

material to buy it or else to make it onsite. Third,

after a source had been found, a method of transporting

the material to the mill site had to be found.

When the first mills were built at both Pacolet and

Glendale, there were no railroad connections to the mill

site. All of the material had to be brought in by horse

and wagons over rough dirt roads. Pacolet Mills No. 1

was built in 1883 and Bivingsville,

now Glendale, in 1837.

It is hard to visualize just how much of the two basic

building materials, lumber and bricks, were needed for

one of the early large mills. Tremendous quantities of

timber were used for the mill frame and floors. Many of

the timber beams had to be huge to support the loads

they carried. The heavy textile machinery vibrated as it

ran, often around the clock. If the mill was not built

strong enough, it could be literally shaken apart.

Probably, much of the timber needed was from trees

felled and sawn close to the vicinity of the mills.

Bricks in quantities of hundreds of thousands or even

millions were needed. At Pacolet, it appears that the

bricks were built at a location close to the village. A

newspaper advertisement exists where Dr. Bivings was

soliciting brick makers and brick masons in 1837 when he

was building the first mill at Bivingsville or what is

now known as Glendale. This same ad also solicits

workers to cut and shape the timber beams used in the

mill. The advertisements are from the Greenville

Mountaineer Newspaper of 1837. One

advertisement from April, 1837 is solicting bricks and

brick masons and other workers for constructing the

mill. The second ad from July, 1837 is announcing that

the mill is in operation and now producing yarn. Both

ads can be read in detail at 1837

Newspaper Advertisements.

Construction of the mill was hard physical labor. Much

of the effort consisted of moving and lifting the tons

of building material. The foundations had to be

constructed down to the bed rock. A weak foundation

could result in the mill collapsing. Some of the very

early mills were made of wood timbers and flooring

placed on stone foundations. Others had exterior walls

made of many layers of brick but used timber for the

interior framing and floors.

In both cases, considerable effort was used in hoisting

the materials to the upper floors. Probably, most of the

lifting was done by the use of ropes and pulleys powered

by men or horses. Mill No. 2 at Pacolet was built in

1888 and was four stories or about 80 feet high. Even

with modern cranes and elevators, moving material to

this height would be difficult. It is amazing that the

builders did this just with men and horsepower.

Another aspect of building with bricks has not been

mentioned. There would be tons of mortar to be mixed,

carried and used to bond the thousands of brick

together. It is possible that the mortar was made right

on the site using lime kilns. These kilns heated

limestone rocks into lime that was used in the mortar.

However, it is more likely that at Pacolet and even

Bivingsville, commercial mortar was used that had been

obtained from Limestone Springs near Gaffney in what is

now Cherokee County. A superior grade of mortar was made

commercially there and shipped all over the South.

The brick masons building the high, multi-story mills

had to be not only skilled in their trade but also

brave. Some of their work involved standing on

rudimentary scaffolding 80 or 100 feet above the ground

- or the Pacolet River.

The dam at

Pacolet No. 3, "the old mill". It was built in 1891

and is still used to generate electric power today.

The dam at

Pacolet No. 3, "the old mill". It was built in 1891

and is still used to generate electric power today.

So far we have discussed building the mill. However, the

all important dam was being built at the same time or

even before the mill building. Building the dam was

truly a dangerous and critical job. Without a dam there

would be no waterpower to run the mill’s

machinery.

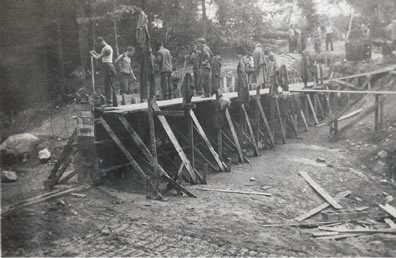

In building the dam, the river had to be first partially

diverted to one side of the channel by blocking the

flow. This was probably done with wagon loads of rocks.

Once this was done, half of the dam could be built in

the “dry” part of the river bed. After half the dam was

complete, the process was repeated and the rest of the

dam was built. The first dam was built for Pacolet Mill

No. 1 in 1883 and was about 100 yards long. This dam

survived the great flood of 1903

and still stands today.

Men building a

dam - location is unknown.

Men building a

dam - location is unknown.

Water flowing

over the upper dam at Pacolet Mills.

Girl Scout, Louise

Paige, with Pacolet Mills No. 5, "the new mill", and

the upper dam in the background.

Girl Scout, Louise

Paige, with Pacolet Mills No. 5, "the new mill", and

the upper dam in the background.

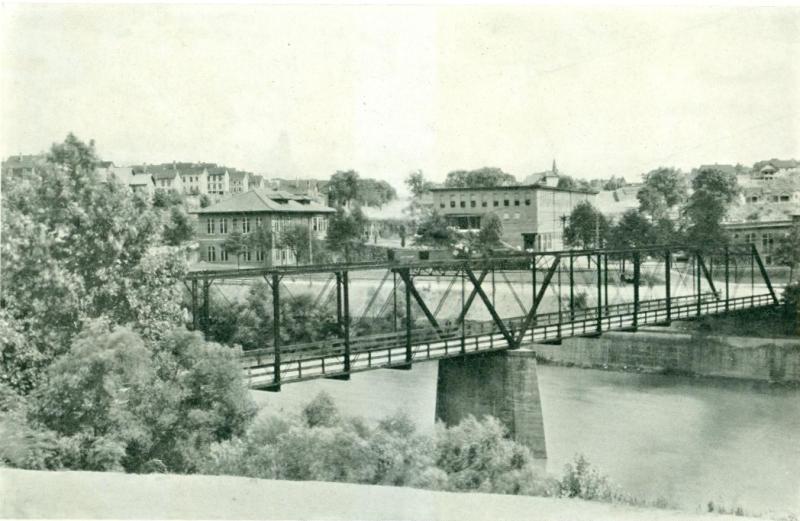

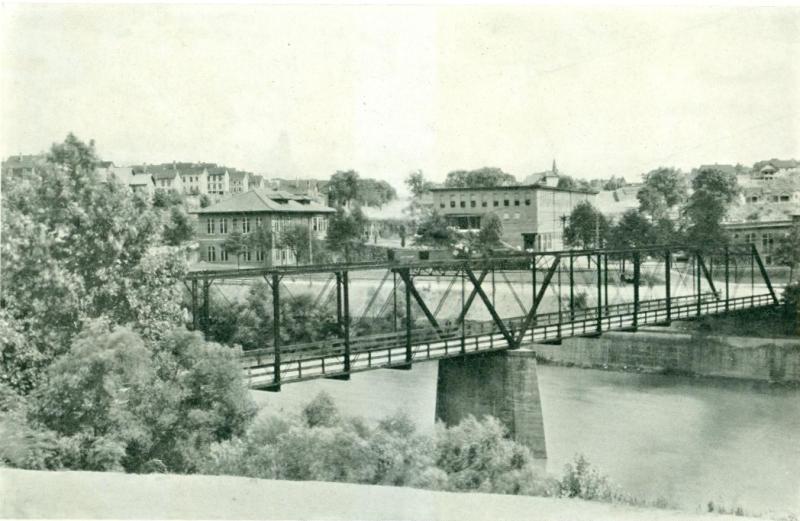

The dam at

Glendale with the old iron bridge in the background.

In the first mills, the purpose of the dams was to

increase the depth of the water and to channel a flow to

the mill’s waterwheel. The waterwheel was the heart of

the mill. There were four big waterwheels for Pacolet

Mills No. 1 and 2. The water made the big wheel rotate.

The wheel was attached to a shaft that went inside the

mill. The rotating shaft was attached to a complex

system of pulleys, smaller line shafts and flat leather

belts. These parts transmitted the power from the

waterwheel to every floor in the mill. Individual

machines such as looms were connected to the belt and

pulley system.

A waterwheel at a

mill. Not at Pacolet or Glendale.

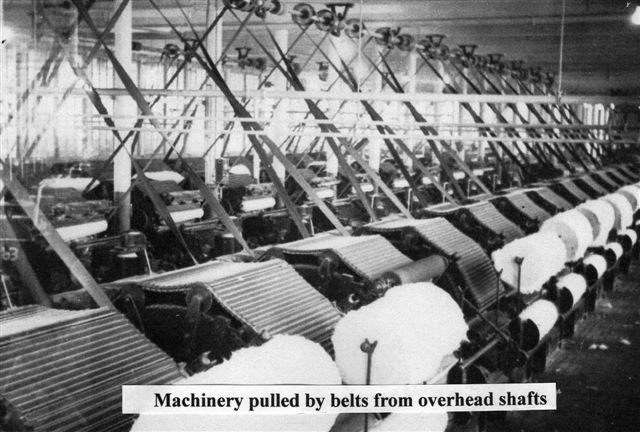

A mill, around 1900, was a complex, noisy scene of

rotating pulleys, line shafts and flat belts. For the

most part, these rotating parts were not covered. A belt

could break, come off a pulley and cause serious injury

or death to a worker.

The textile machinery used in the mills around 1900 was

probably the most elaborate and complex machines that

existed anywhere at the time. They were a mass of gears,

pulleys, levers, cams and belts. All of this was usually

contained within a very heavy cast iron frame. Some of

these machines weighed several tons. Textile machinery

was always in the forefront of technology. Our modern

computers and coded data instructions can be traced back

to the Jacquard Loom invented in 1801. This machine used

cards with punched holes to control the loom to weave

cloth with complex patterns.

Mill machines not only had to have skilled operators

they also have skilled maintenance and repair workers to

keep them performing properly. Keeping the machinery up

and running was a full time job for many workers.

One of the unsung wonders of the Upcountry textile

industry was the recruiting and training of thousands of

rural workers to operate and maintain the truly complex

machinery of a textile mill.

Overtime, waterwheels were replaced with steam engines

and eventually electric motors. However, for a long

time, the system of pulleys, belts and line shafts were

still used with the new power sources. They were in use

generally until the around 1940’s when new machinery was

installed in the mills that had their own individual

motors.

The construction of the mill and dam was a very

important part of the project but it was not all. A

place had to be provided for the workers to live. In the

era before cars, it meant that the workers had to live

close to the mill. To allow this, the owners had to

build an entire small town or village around the mill.

This involved building houses for several hundred

workers, roads, a school, a church, a post office, a

store and other facilities. In a period of two years or

so, an open area of farmland was turned into a new town

and manufacturing operation that gave several hundred

badly needed jobs.

Some of the

houses and other facilities at Pacolet Mills.

Some of the

houses and other facilities at Pacolet Mills.

Building a textile mill like those at Pacolet and

Glendale in the 1800’s was a supreme expression of faith

and confidence on the part of the owners and founders.

For the most part, this meant starting a new operation

where it was unknown and not widely familiar. The

following questions loomed over the heads of the first

builders. -

How will you finance the building of the mill?

Where would you find the people to design and build your

mill?

Where could you find a cheap reliable supply of cotton

in the quantity you need?

In a rural area populated by farmers, where will you

find the hundreds of workers that will be needed to

operate the complex, dangerous machinery?

Where will your workers live? Lack of transportation

means that they will have to live close to the mill.

Where will you find a reliable market for the cloth you

make?

How will you transport the raw cotton and finished

textiles to and from the mill site that only has rough

dirt roads?

These were just some of the troubling questions that had

to be answered for every one of the numerous textile

mills that sprang up in the Carolina Piedmont in the

late 1800’s In spite of all these uncertainties, the

early mill builders, owners and workers pressed on,

survived and created the once booming textile industry

of the Piedmont.